Visualizing spatial data with ggplot2

Session 2

2023-09-06

1 Overview

- Why and how do we visualize spatial data?

- What is the “grammar of graphics”?

- How to use ggplot2 to

- build layered data visualizations

- visualize spatial data

1.1 Why and how do we visualize spatial data?

Why do we visualize spatial data?

- Validation

- Exploration

- Communication

Why do we visualize data?

- Validation

- Exploration

- Communication

Anscombe’s quartet

| set | x | y | set | x | y | set | x | y | set | x | y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 10 | 8.04 | II | 10 | 9.14 | III | 10 | 7.46 | IV | 8 | 6.58 |

| I | 8 | 6.95 | II | 8 | 8.14 | III | 8 | 6.77 | IV | 8 | 5.76 |

| I | 13 | 7.58 | II | 13 | 8.74 | III | 13 | 12.74 | IV | 8 | 7.71 |

| I | 9 | 8.81 | II | 9 | 8.77 | III | 9 | 7.11 | IV | 8 | 8.84 |

| I | 11 | 8.33 | II | 11 | 9.26 | III | 11 | 7.81 | IV | 8 | 8.47 |

| I | 14 | 9.96 | II | 14 | 8.10 | III | 14 | 8.84 | IV | 8 | 7.04 |

| I | 6 | 7.24 | II | 6 | 6.13 | III | 6 | 6.08 | IV | 8 | 5.25 |

| I | 4 | 4.26 | II | 4 | 3.10 | III | 4 | 5.39 | IV | 19 | 12.50 |

| I | 12 | 10.84 | II | 12 | 9.13 | III | 12 | 8.15 | IV | 8 | 5.56 |

| I | 7 | 4.82 | II | 7 | 7.26 | III | 7 | 6.42 | IV | 8 | 7.91 |

| I | 5 | 5.68 | II | 5 | 4.74 | III | 5 | 5.73 | IV | 8 | 6.89 |

A little hard to read!

Take a look at the data using some summary statistics:

| set | x_mean | y_mean | x_sd | y_sd | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 9 | 7.5 | 3.3 | 2 | 0.82 |

| II | 9 | 7.5 | 3.3 | 2 | 0.82 |

| III | 9 | 7.5 | 3.3 | 2 | 0.82 |

| IV | 9 | 7.5 | 3.3 | 2 | 0.82 |

Now, take another look using a plot:

1.2 How do we visualize spatial data?

A map is a special type of data visualization for spatial data but it isn’t the only one.

Plots and tables are other common ways to visualize spatial data.

Visuals can be further transformed using animation and interactivity.

Maps, graphics, and tables also vary in format: print, web, mobile, etc.

2 What is the “grammar of graphics”?

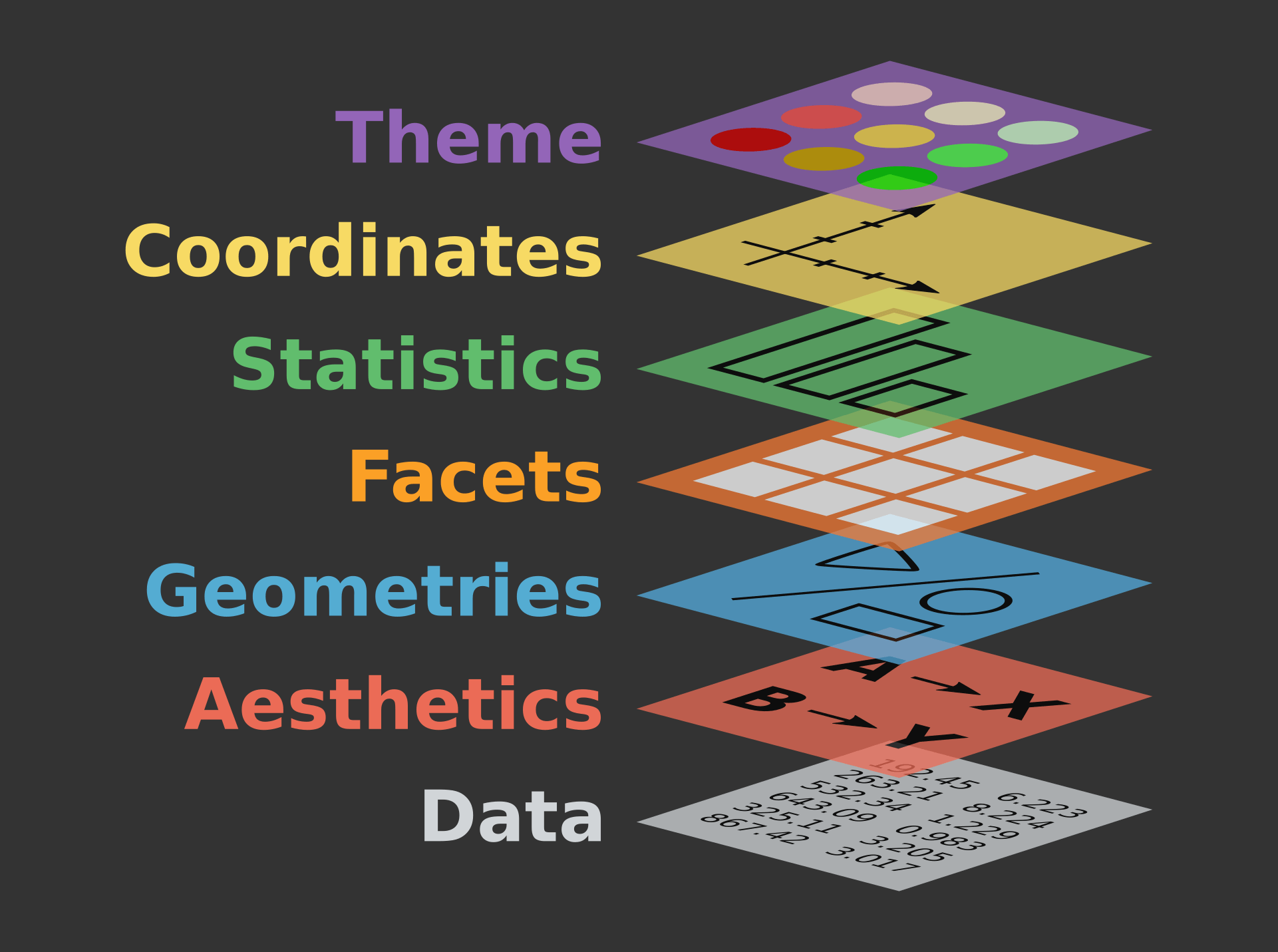

Grammar of graphics

From The Grammar of Graphics for Introduction to data visualisation with ggplot2 QCBS R Workshop Series.

Grammar of graphics

- Data

- Mapping

- Statistics

- Scales

- Geometries

- Facets

- Coordinates

- Theme

Introduction to the “grammar of graphics” adapted from a 2020 ggplot2 workshop (part 1) by Thomas Lin Pedersen.

2.1 Data

- Structure and representation of data determines what you can and can’t do with it

- Data is expected to be in a “tidy” format (a.k.a. long format data)

A few definitions:

- variable: a quantity, quality, or property that you can measure.

- value: the state of a variable when you measure it. The value of a variable may change from measurement to measurement.

- observation: a set of measurements made under similar conditions

- tabular data: a set of values, each associated with a variable and an observation.

What works best with the grammar of graphics is tidy data:

- each value is placed in its own “cell”,

- each variable in its own column, and

- each observation in its own row.

2.2 Mapping

-

Mapping allows data to be understood by the graphics system

- Aesthetic mapping: variables -> graphical properties in the geometry

- Facet mapping: variables -> panels in layout

2.3 Statistics

Data may not represent the displayed values

-

Statistics transform input variables into displayed values, e.g.

- Counting the number of observations by category

- Calculating summary statistics for a boxplot

Statistics can be used prior to plotting data or used by a plotting function directly.

2.4 Scales

-

Scales translate between value ranges and graphical properties, e.g.

- Categories -> Colors

- Numbers -> Position

Scales use a specific type of interpolation, e.g. discrete, continuous, etc., so not all scales work with all variables.

In the not too common case where data directly represents a graphical property, e.g. a “color” column, you can use a special type of scale called an “identity” scale.

2.5 Geometries

How translate aesthetics into graphical representations

Basic geometries (e.g. points, lines, polygons) can be combined into more complex geometries (e.g. box plot, map)

Typically, the geometries are the same as the “type” of plot

2.6 Facets

- Defines how data is split across multiple panels

2.7 Coordinates

Positional aesthetics must be interpreted by a coordinate system

Defines the physical mapping of aesthetics to the paper

We usually think about the cartesian coordinate system—but there are a lot of different kinds of coordinate systems.

2.8 Theme

-

Every other part of the graphic that isn’t linked to the data:

- Fonts

- Spacing

- Colors

- Weights

- etc.

3 How to to use {ggplot2} to…

- build layered data visualizations

- visualize spatial data

3.1 Cheatsheets

3.2 Build layered data visualizations

3.3 Setup

For this session, we are going to use the ggplot2 and dplyr packages along with sf and rnaturalearth:

3.4 Setup data

Next, we are going to use the storms data included with dplyr.

Take a quick look at storms using glimpse():

glimpse(storms)

#> Rows: 20,778

#> Columns: 13

#> $ name <chr> "Amy", "Amy", "Amy", "Amy", "Amy", "Am…

#> $ year <dbl> 1975, 1975, 1975, 1975, 1975, 1975, 19…

#> $ month <dbl> 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6,…

#> $ day <int> 27, 27, 27, 27, 28, 28, 28, 28, 29, 29…

#> $ hour <dbl> 0, 6, 12, 18, 0, 6, 12, 18, 0, 6, 12, …

#> $ lat <dbl> 27.5, 28.5, 29.5, 30.5, 31.5, 32.4, 33…

#> $ long <dbl> -79.0, -79.0, -79.0, -79.0, -78.8, -78…

#> $ status <fct> tropical depression, tropical depressi…

#> $ category <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA…

#> $ wind <int> 25, 25, 25, 25, 25, 25, 25, 30, 35, 40…

#> $ pressure <int> 1013, 1013, 1013, 1013, 1012, 1012, 10…

#> $ tropicalstorm_force_diameter <int> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA…

#> $ hurricane_force_diameter <int> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA…Remember! Each row is an *(observation** of a storm, not a individual storm.

storms is a subset of a larger Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT2) with data from 1851 to 2022.

Since 1974, NOAA’s Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite program has played a key role in tracking storms and monitoring weather around the world.

3.5 Create a ggplot

We can start by using the function ggplot() to define a plot object. Set storm as the input data for ggplot():

Well, that doesn’t look like much. 🤔

This is the first step in creating a plot that we can add layers to. Parameters set with ggplot() are inherited by layers added later.

3.6 Add aesthetics and layers

Set mapping with aes()

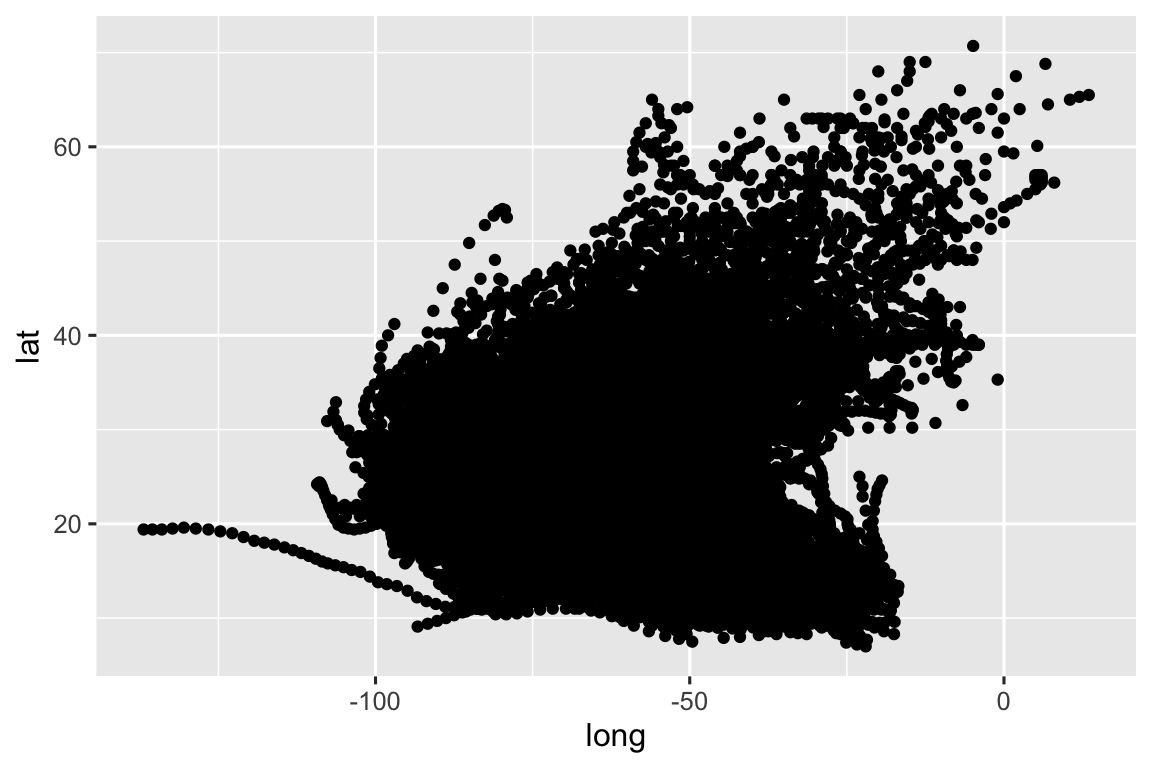

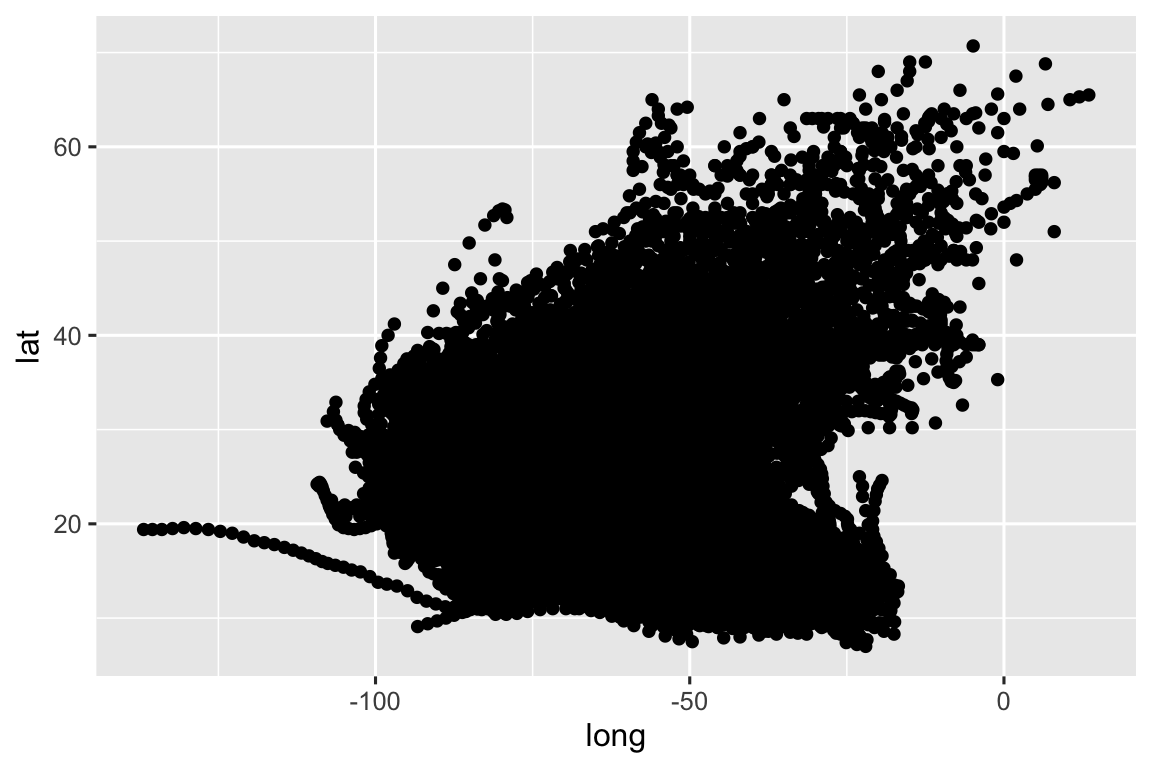

Next, we can set the mapping using the aes() function. We can start by mapping long (longitude) to x and lat (latitude) to y:

Before we can see any data, we need to tell ggplot() how we want to represent the data using layers.

Layers in ggplot2 are most often added using “geoms” (short for geometry) functions like geom_point(), geom_col(), or geom_histogram().

Let’s give it a try using geom_point():

You can define the data and mapping parameters globally using ggplot() or locally for a single geom function. This code does the exact same thing as the prior block:

What is this + operator?

Notice that we are combining the ggplot() and geom_point() functions using the + operator.

This is a style of function or operator known as an infix operator.

This operator works is similar to the pipe operator, %>% or |> that passes the output from one function (or line of code) to the next line as the first parameter in a following function.

For example, see how we can use a series of pipes to operate on the storms data:

The prior block is the same as the following block:

Using pipes can help avoid the need for intermediate objects like storm_names that might only exist to move the output of one function to the input for another function.

The first parameter for ggplot() is data and the first parameter for all geom functions is mapping so you often see these passed as unnnamed parameters:

You can even leave off the x and y parameter names:

Mapping variables are not strings!

The variables passed to aes() don’t have quotes around them! This is because aes() is a data-masking (also known as a quoting function) where the inputs are evaluated in the context of the data.

TLDR: only put quotes around your aesthetic mappings when you want to pass a literal string.

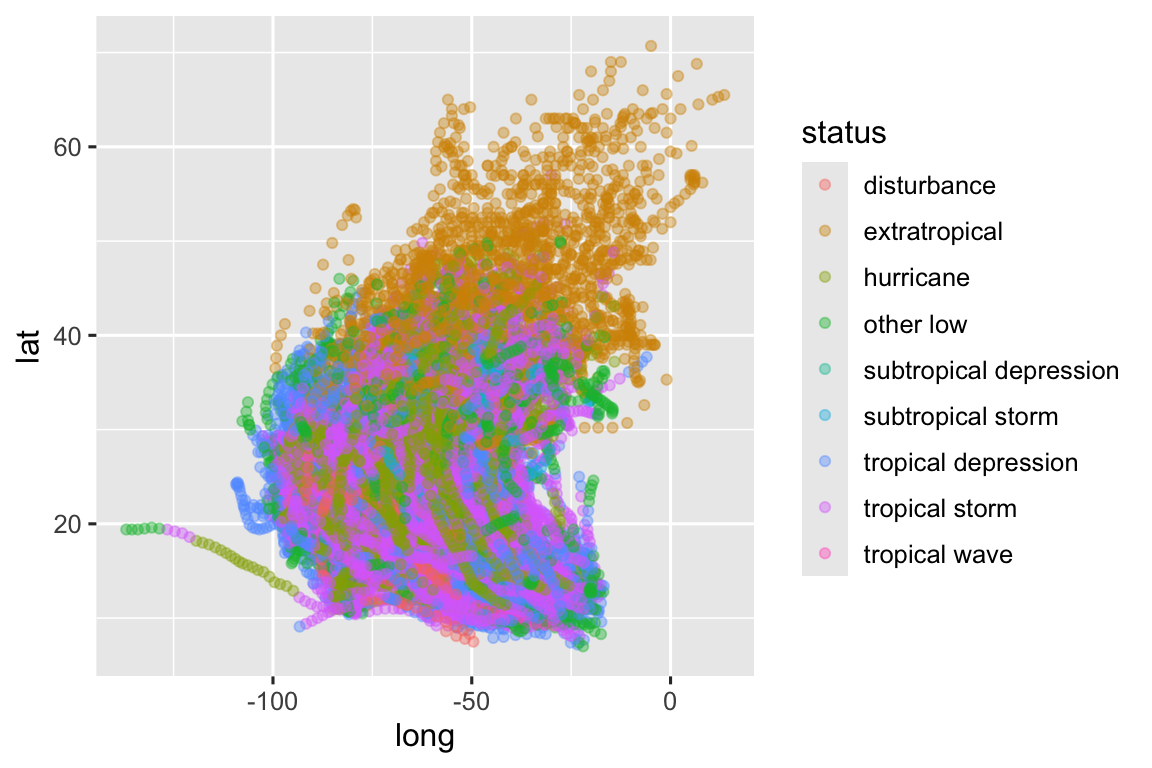

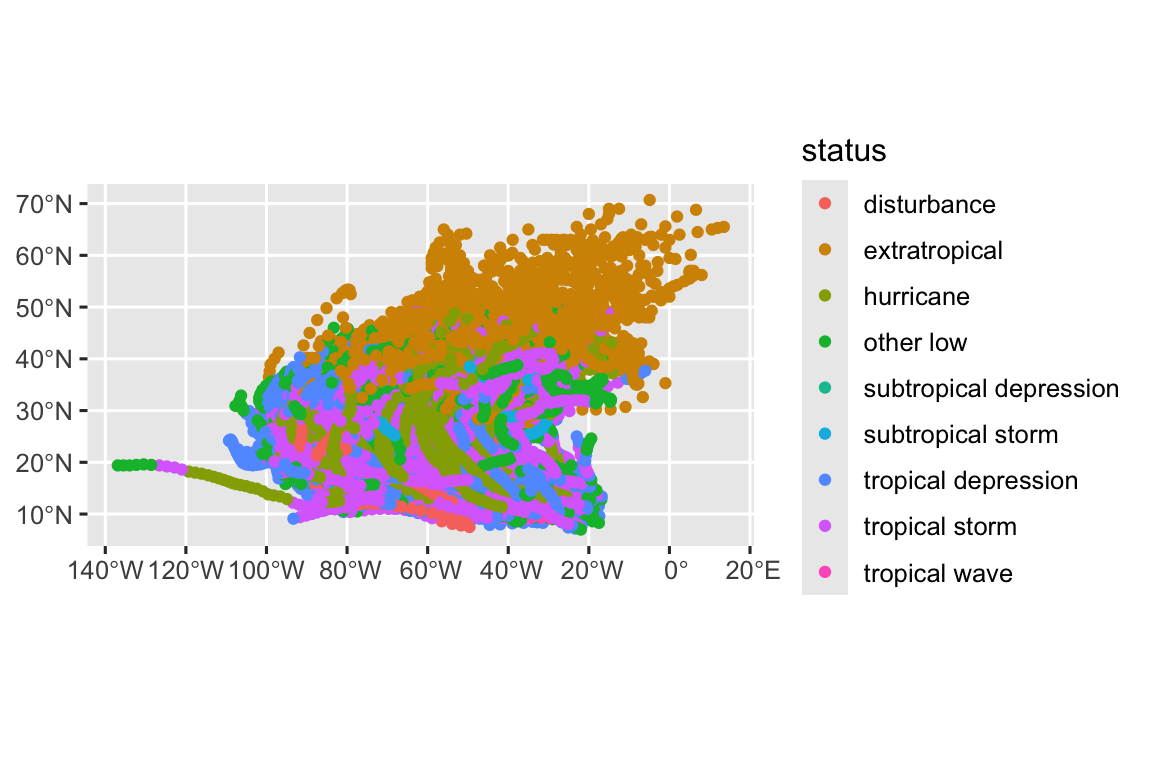

Next we can map one of the variables (status or storm classification) to an aesthetic (color):

Note that we now have a legend, added automatically when we defined a mapping to color. Since color is not a “positional aesthetic” we can’t easily interpret the meaning of the graphic without a legend, labels, or annotations.

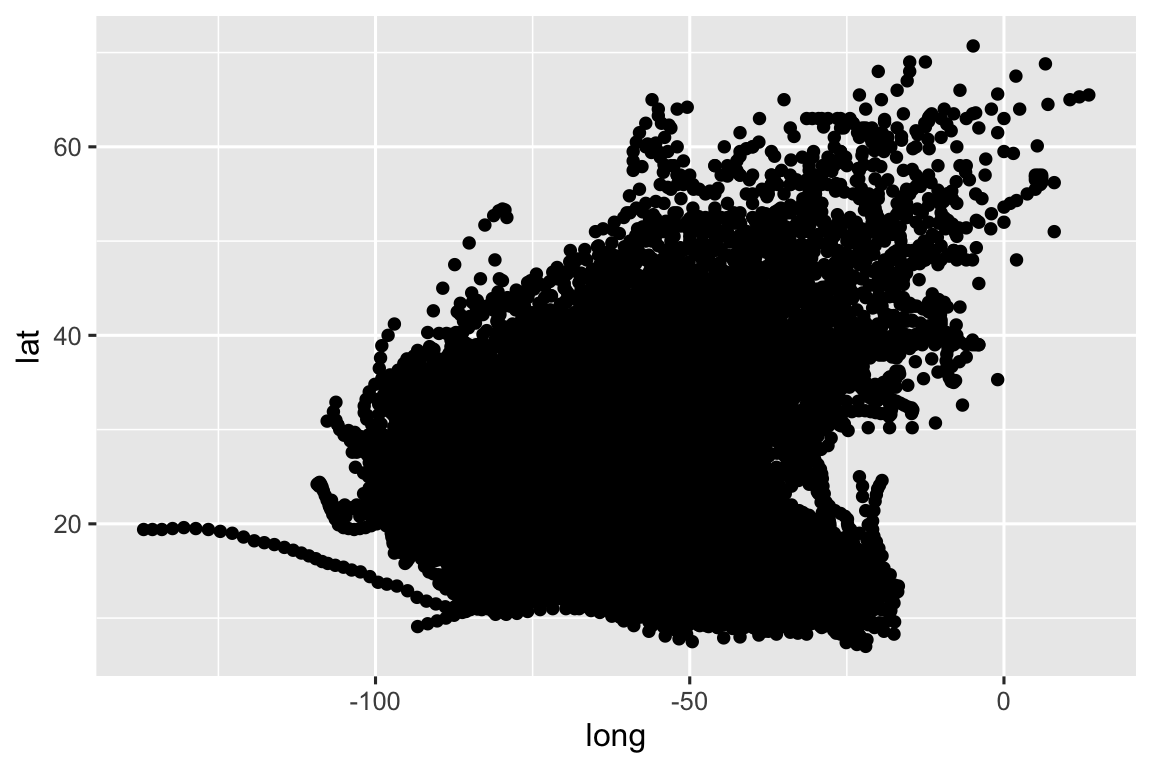

In addition mapped aesthetics, we can set “fixed” aesthetics (called fixed because the same value is used for every observation in the plot).

When you have a lot of overlapping features (known as overplotting), you may want to reduce the alpha (or transparency) of the features:

Fixed aesthetics should be defined for each geom—they are ignored if you pass them to ggplot().

Aesthetics can also be defined using a function. In this example, we are using the boolean operator == to compare the values from “status” to the string “hurricane”:

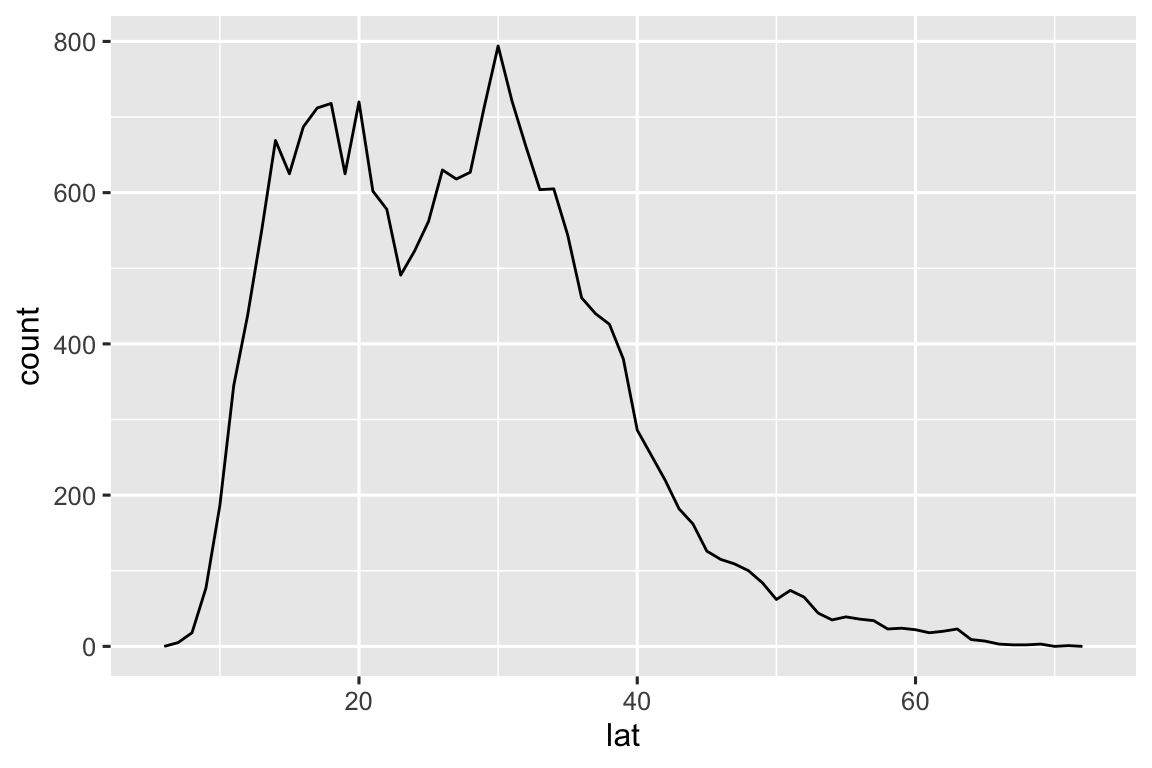

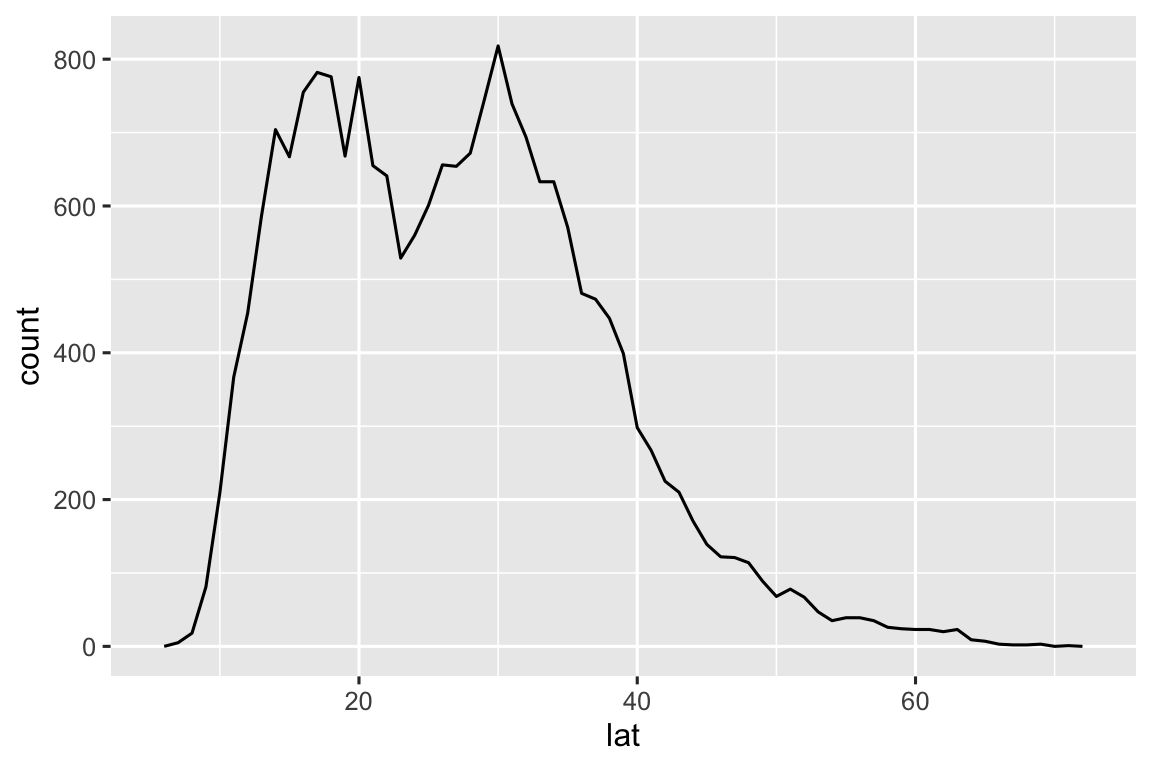

3.7 Visualizing distributions

3.8 Distribution of one numeric variable

3.9 Distribution of one numeric variable

3.10 Distribution of one categorical variable

4 Visualize spatial data

To start, let’s convert our storms data set from a data frame into a sf object using sf::st_as_sf():

Always supply coordinates with longitude before latitude!

sf::st_as_sf() requires that you supply coordinates in lon lat order. This is also the standard order for GeoJSON files, Shapefiles, and KML files. Check out lon lat lat lon by Tom MacWright for more information.

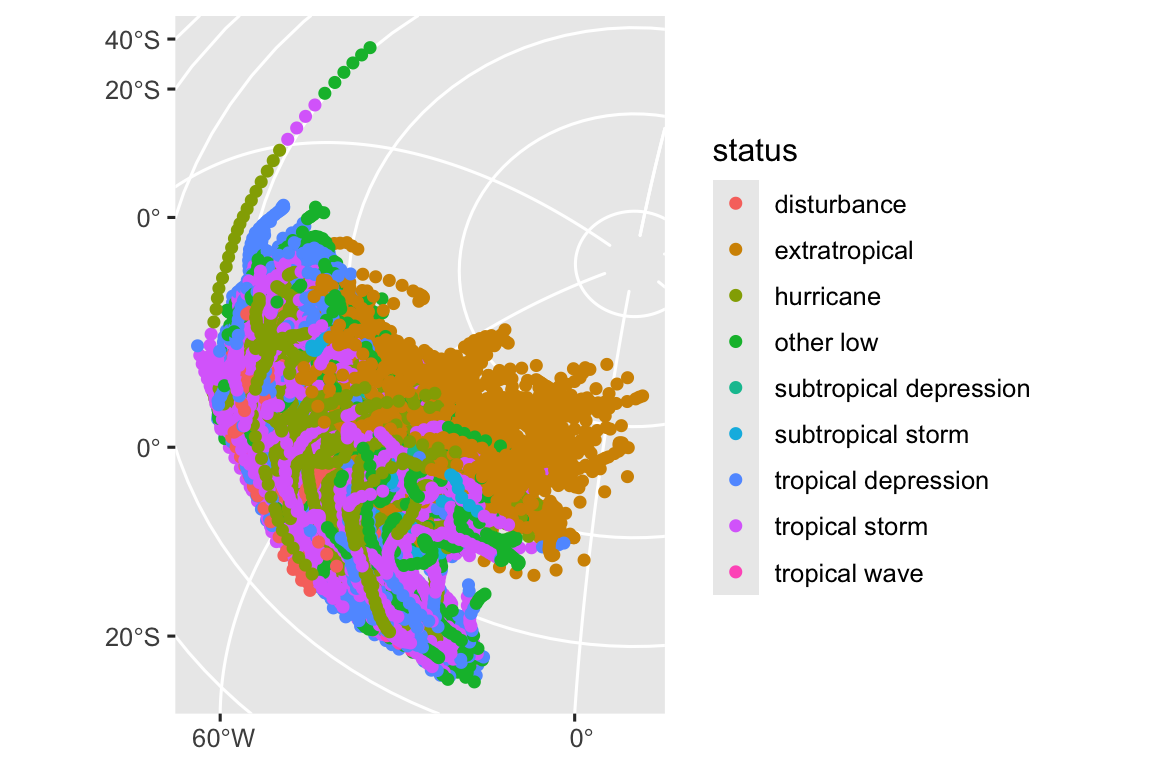

Finally, we can look at these observations on a map:

That first map may not look much different.

But converting the data to a sf object allows us to use coord_sf() to transform the coorindate reference system on the fly:

This is equivalent to converting the coordinate reference system in advance using st_transform():

Note, that this is another example of how we can use the pipe (|>) to move data between functions in R.

However, to really show the potential, we need some more data. Install and load the rnaturalearth package and then load data for the coastline and countries:

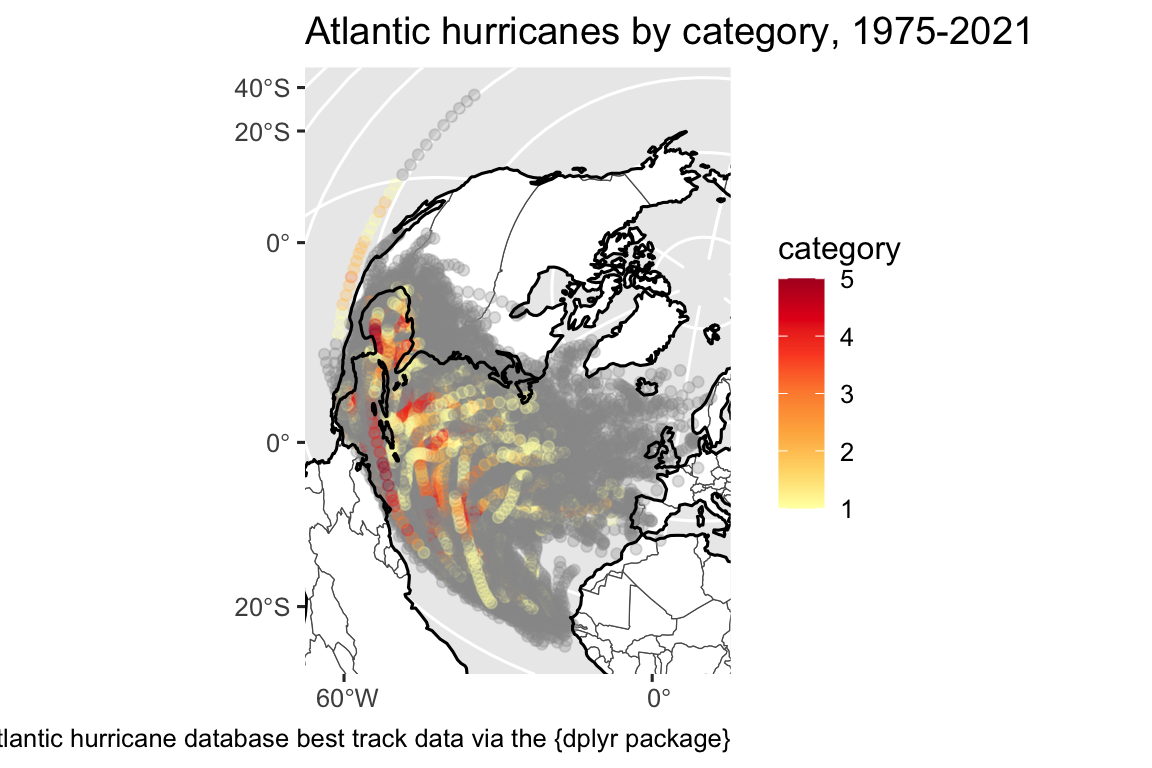

Put them together and we are starting to get somehwere:

But the map is zoomed out to show the whole world—not just the north Atlantic storm observations. We can use the xlim and ylim parameters of coord_sf() to “zoom” in on a smaller area:

storms_bbox <- storms_sf |>

st_transform("EPSG:3035") |>

st_bbox()

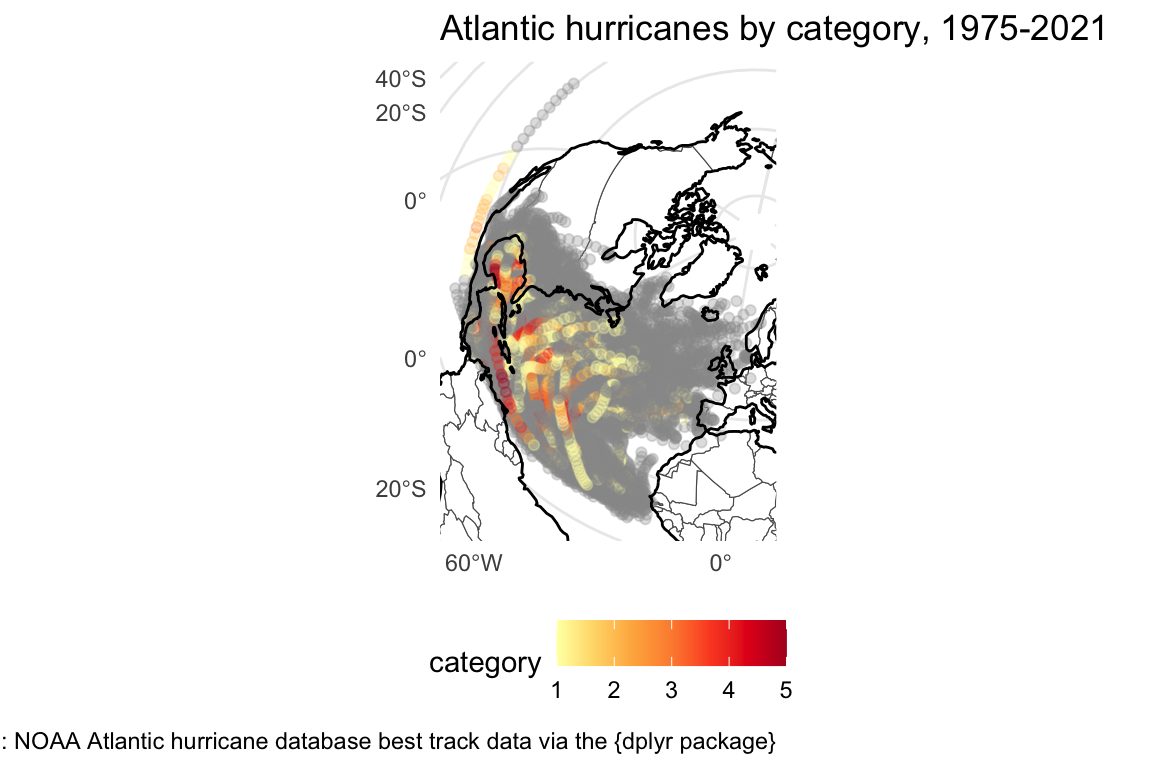

storms_map <- ggplot() +

geom_sf(data = countries, fill = "white") +

geom_sf(data = storms_sf, aes(color = category), alpha = 0.3) +

geom_sf(data = coastline, color = "black") +

coord_sf(

xlim = c(storms_bbox$xmin, storms_bbox$xmax),

ylim = c(storms_bbox$ymin, storms_bbox$ymax),

crs = "EPSG:3035"

)

storms_map

Try adding a scale:

Now try adding some labels:

Lastly, we can adjust the theme:

“It’s true that there are better and worse ways to make a map but no one way to make an excellent map.”

Gretchen N. Peterson in GIS Cartography: A Guide to Effective Map Design

What makes a bad map bad?

For new map makers who might not know any better, it is often:

- Confusing or distracting layout

- Not enough color contrast for features

- Cluttered labels, legends, or features

What makes a fine map just fine?

For more experienced map makers who might be in a hurry: - Not enough thought on font sizes and styling - No feature generalization (simplifying geometry where appropriate for the map scale or subject) - Inappropriate color scales

Other related considerations

There are many cartographic considerations that also apply to other all types of data visualization:

- Layout

- Fonts (Typography)

- Colors

- Output formats

Other cartography considerations

But there are also some cartographic considerations that apply to maps in special and important ways:

- Feature geometry (and cartographic conventions)

- Projections

- Scaling